![]()

SELECTED DOCUMENTS FROM THE

TÜBINGEN INTERFAITH DIALOGUE

“World Religions as a Factor in World Politics”

7-8 May 2007, Tübingen, Germany

The Three Abrahamic Religions

Historical Upheavals – Present Challenges

Speech by Professor Hans Küng

Professor Emeritus, Tübingen University

Ⅰ. The abiding centre and foundation

Ⅱ. Epoch-making upheavals

Ⅲ. Present-day challenges

Ⅳ. The three religions contribute to a global ethic

Introduction

We face the threat of a general suspicion - this time not of Jews but of Muslims. It is as if they were all incited up by their religion, and were all potentially violent. Whereas conversely, Christians, because they are taught by their religion, are all seen as non-violent, peaceful and loving... That would be a fine thing!

Of course there are many problems, especially in Europe with its big Muslim minorities, but Let’s be fair: of course we citizens of a democratic constitutional state reject forced marriages, the oppression of women, honour killings and other archaic inhumanities in the name of human dignity. But most Muslims join us in doing so. They suffer from the fact that the condemnations made are sweepingly of the “Muslims” and the “Islam”, without differentiation. They do not recognise themselves in our picture of Islam, because they want to be loyal citizens of the Islamic religion.

Let’s be fair: those who make “Islam” responsible for kidnappings, suicide attacks, car bombs and beheadings carried out by a few blind extremists ought at the same time to condemn “Christianity” or “Judaism” for the barbarous maltreatment of prisoners, the air strikes and tank attacks (several 10,000 civilians have been murdered in Iraq alone) carried out by the US Army, and the terrorism of the Israeli army of occupation in Palestine. After three years of war also a majority of Americans realise that those who pretend that the battle for oil and hegemony in the Middle East and elsewhere is a “battle for democracy” and a “war against terror” are trying to deceive the world - though without success.

In the 3rd Global Ethic Lecture in Tübingen in 2003 the UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan emphasised: “No religion or ethical system should ever be condemned because of the moral lapses of some of its adherents. If I, as a Christian, for instance, would not wish my faith to be judged by the actions of the Crusaders or the Inquisition, I should be very careful to judge anyone else’s faith by the actions that a few terrorists may commit in its name”.

So I am asking you: Should we go on with a tit-for-tat reckoning which leads only deeper into misery?

No, another basic attitude to violence and war is called for. And basically people everywhere want it, unless - in the Arab countries and sometimes also in the USA - they are being led astray by power- obsessed and blind governments and are having their minds dulled by ideologues and demagogues in the media.

Violence has been practiced in the sign of the crescent, but also in the sign of the cross, by mediaeval and contemporary “crusaders”, who perverted the sign of reconciliation, the cross, so that it became a sign of war against Muslims and Jews (Spain). Both religions Christianity and Islam have expanded their spheres of influence aggressively in history and defended their power with violence. In their sphere they have propagated an ideology, not of peace, but of war. So the problem is a complicated one.

We are all in danger of being inundated by the gigantic floods of information and thus losing our bearings. And one can sometimes hear even scholars of religion expressing the opinion that, in their own discipline, it is hardly possible to see the woods for the trees. So some of them - as for example in sociology - concentrate on micro-studies and are no longer prepared to think in wider contexts; or they are no longer capable of it. Here, I believe, new categories are necessary to embrace the changes.

So I shall attempt to offer you in a little more than one hour a certain basic orientation on Islam the three Abrahamic religions, Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. To get straight to the point: I want to address three complexes of questions: I. The abiding centre and foundation, what must unconditionally be preserved: II. Epoch-making upheavals: what can change; III. Present-day challenges: the tasks that press in on us.

I. The abiding centre and foundation

This is a very practical question: What should be preserved, what should be unconditionally preserved, in each of our religions? In all three prophetic religions there are extreme positions: some say “Nothing just this should be preserved”, while others say “Everything, really everything should be preserved”:

– Completely secularised Christians say that “nothing” should be preserved: they often do not believe either in God or in a Son of God, they ignore the church and dispense with preaching and sacraments.

At best they treasure the cultural heritage of Christianity: the European cathedrals or Johann Sebastian Bach; the aesthetics of the Orthodox liturgy or also paradoxically the Pope, the pope as a pillar of the established order, though of course they reject his sexual morality and authoritarianism and sometimes are agnostics or atheists.

– But completely secularised Jews also say that “Nothing should be preserved”: they think nothing of the God of Abraham and the patriarchs, they do not believe in his promises, they ignore synagogue prayers and rites and ridicule the ultra-Orthodox.

They have often found a modern substitute religion for their Judaism which has been evacuated of religion: the state of Israel and an appeal to the Holocaust. This also creates a Jewish identity and solidarity for secularised Jews, but often at the same time seems to justify a state terrorism against Arabs which is contemptuous of human rights.

– And completely secularised Muslims also say that “Nothing should be preserved”. They do not believe in one God, they do not read the Qur’an, Muhammad is not a prophet for them and they roundly reject the Shariah; the five pillars of Islam play no role for them.

At best Islam, of course emptied of its religious content, is to be used as an instrument for a political Islamism, Arabism and nationalism.

You certainly understand now that as a counter-reaction to this “Preserve nothing” the opposite cry can be heard: “Preserve everything”. Everything is to remain as it is and allegedly always was.

“Not a stone of the great edifice of Catholic dogma may be torn down; the whole structure would totter” trumpet Roman integralists [and traditionalists].

“Not a word of the halakhah may be neglected; the will of the Lord (Adonai) stands behind every word”, protest ultra-Orthodox Jews.

“Not a word of the Qur’an may be ignored, each is in the same way directly the word of God”, insist many Islamist Muslims.

You see: Here conflicts are pre-programmed everywhere, not just between the three religions, but above all in them, wherever these positions are advocated militantly or aggressively: often the extreme positions goad each other on.

But be sure, reality doesn’t look quite so gloomy. For in most countries, if they are not loaded with political, economic and social factors, the extreme positions do not form the majority. There are always a considerable number of Jews, Christians and Muslims - of different magnitudes of course depending on the country and the time

- who although often indifferent, lazy or ignorant in their religion, by no means want to give up everything in their Jewish, Christian or Muslim faith and life. On the other hand, though, they are not prepared to keep everything: many Catholics do not swallow all the dogmas and moral teachings of Rome and many Protestants do not take every statement in the Bible literally; many Jews do not observe the Halakhah in all things; and many Muslims do not observe all the commandments of the Shariah strictly.

Be this as it may: if we don’t look at some later historical forms and manifestations, but reflect on the foundation documents, the original testimonies, I mean the “holy scriptures” of each religion - if we look at the Hebrew Bible, New Testament and Qur’an - there can be no doubt that the “abiding” (that which must abide) in the religion concerned is not simply identical with the “existing” (what exists at the time); and that what makes up the “nucleus”, the “substance”, the “essence” of this religion can be defined by its “holy scriptures”.So the question here is quite a practical one: what should be the abidingly valid and constantly binding element in each of our own religions? It should be clear that not everything need be preserved, but what must be preserved is the substance of faith, the centre and foundation of the religion concerned, its holy scripture, its faith! As John XXⅢ formulated in his famous opening speech to the 2nd Vatican Council, in which I participated as theological Adviser, together with my dear colleague Josephe Ratzinger, now Pope Benedict XVI, as the two teenager theologians! But you ask me some more concrete questions, and I give you very brief but basic answers:

You may ask me

1.What must be preserved in Christianity if it is not to lose

its “soul”? My answer: no matter what historical, literary or sociological biblical criticism may criticize, interpret and reduce: [in the light of the Christian foundation documents of faith which have become normative and influential in histroy;] in the light of the New Testament (seen in the context of the Hebrew Bible), the central content of faith is Jesus Christ: as the Messiah and Son of the one God of Abraham who is also at work today through the same Spirit of God. There can be no Christian faith, no Christian religion, without the confession “Jesus is the Messiah, Lord and Son of God!” [1.Kor:Iltous kyrios]. The name Jesus Christ denotes the dynamic “centre of the New Testament” (which is by no means to be understood in a static way).

You ask me

2.What must be preserved in Judaism if it is not to lose its “essence”?

My answer: no matter what historical, literary or sociological criticism may criticise, interpret and reduce: [in the light of the foundation documents of faith which have become normative and historically influential,] in the light of the Hebrew Bible, the central content of faith is the one God and the one people of Israel. There can be no Israelite faith, no Hebrew Bible, no Jewish religion without the confession: “Yahweh (Adonai) is the God of Israel, and Israel is his people!”

And you ask me

3.And what finally must be preserved in Islam, if it is still to remain

“Islam” in the literal sense of “submission to God”? My answer: no matter how wearisome the process of collecting, ordering and editing the different surah of the Qur’an was, for all believing Muslims it is clear that the Qur’an is God’s word and book. And even if Muslims see a difference between the Mecca surah and those of Medina and take the background of the revelation into account for interpretation, the central message of the Qur’an is completely clear: “There is no God but God, and Muhammad is his Prophet”. It is the special relationship of the people of Israel to its God (that is the essence of Judaism). And it is the special relationship of Jesus Christ to his God and Father (that is the starting point of Christianity). And it is the special relationship of the Qur’an to God that is the nucleus of Islam, which constitutes it and around which it crystallises. And despite the goings back and forth in the history of the Islamic people, this will remain the basic notion of Islamic religion which will never be given up.

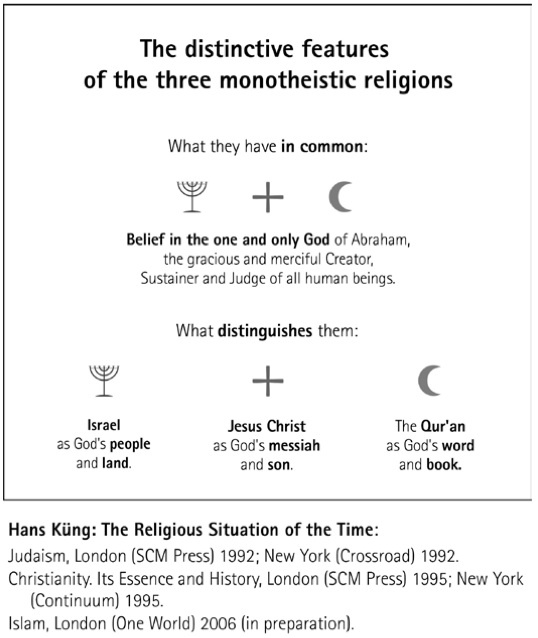

The distinctive feature of the three monotheistic religions which is to be preserved is something that they have in common and at the same time something that distinguishes them.

- – What have Judaism, Christianity and Islam in common?

Faith in the one and only God of Abraham, the gracious and merciful Creator, Preserver and Judge of all human beings. Not a cyclical view of world history and individual life, but oriented towards an end; the importance of prophetic figures, a normative scripture and common ethical standards.

- – And what distinguishes them?

- For Judaism: Israel as God’s people and land (essential for Israel). For Christianity: Jesus Christ as God’s Messiah and Son.

For Islam: the Qur’an as God’s word and book.

- In the constant centre of the three religions, of Judaism as of

- Christianity and finally of Islam, is grounded:

- – Originality from earliest times,

- – Continuity in its long history down the centuries,

- – Identity despite all the difference of languages, peoples, cultures

- and nations.

However, this centre, this foundation, this substance of faith never existed in abstract isolation, but in history: it has time and again been reinterpreted and realised in practice in the changing demands of time. Toynbee: challenge and response! For theologians, historians and others it is important to combine a systematic-theological with a historical-chronological description, without which the former cannot be given a convincing foundation.

II. Epoch-making upheavals

Again and again new epoch-making constellations of the time - society generally, the faith community, the proclamation of the faith, and reflection on the faith came up in the history of the three religions and reinterpreted and concretised this one and the same centre. In Judaism, Christianity and Islam this history is extraordinarily dramatic: In response to ever new and great challenges in world history the community of faith, at first small but then - particularly in the case of Christianity and Islam - growing quickly, has undergone a whole series of religious changes, indeed in the longer term revolutionary paradigm shifts. This concept I learned from a historian of sciences, Thomas S. Kuhn, “The Structure of Scientific Revolutions” (1962): What changed in the Copernican Revolution? The sun, the moon, the stars remained the same, but we changed: our way to look at them, our world view - the paradigm: The entire constellation of beliefs, values, techniques, and so on, shared by a given community”. I applied the paradigm theory to the history first of the church then of the different religions. What changed e.g. in the Reformation? God, Christ, the Spirit for Christians remained the same. But the view of the believers changed: the paradigm, the models.

The historical analysis of the paradigms of a religion, those macro- paradigms or epoch-making overall constellations, serves to orientate knowledge. Paradigm analysis makes it possible to work out the great historical structures and transformations: by concentrating on both the fundamental constants and the decisive variables at the same time. In this way, it is possible to describe those breaks in world history and the epoch-making basic models of a particular religion which emerged from them.

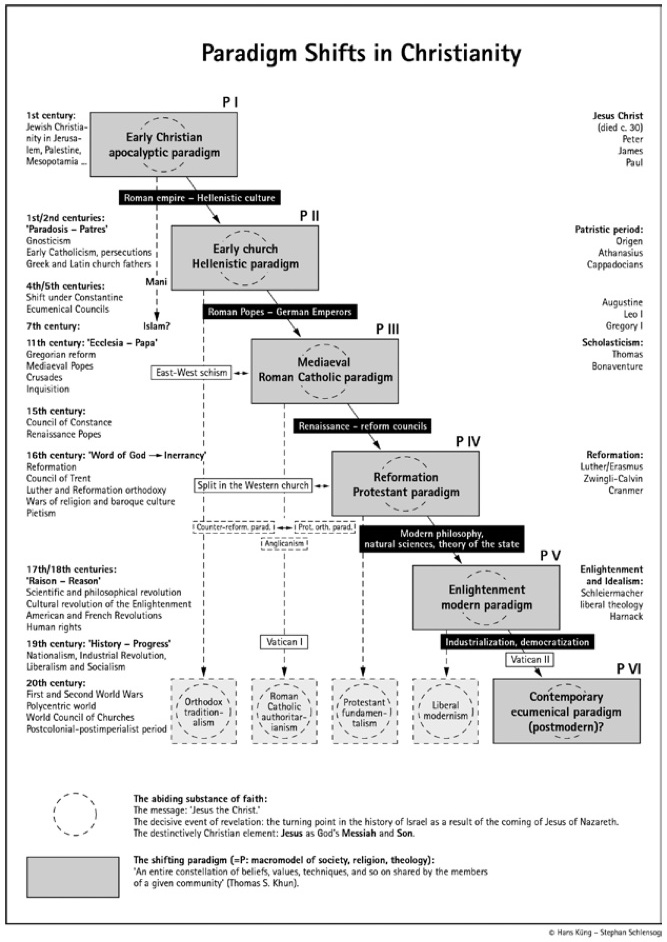

So against the background of such a considerable history, a historical- systematic analysis of its epoch-making overall constellations must be attempted. In my book, Christianity I worked out the macro-paradigms in the history of

A. Christianity (cf. diagram): I am now referring to the diagram you have in your hands, especially to the outline:

- I: the Jewish apocalyptic paradigm of earliest Christianity;

- II: the ecumenical Hellenistic paradigm of Christian antiquity;

- III: the medieval Roman Catholic paradigm;

- IV: the Protestant paradigm of the Reformation;

- V: the paradigm of modernity oriented on reason and progress;

- VI: the ecumenical paradigm of post-modernity?

First insight: Every religion does not appear as a static entity, in which allegedly everything always was as it is now. Rather, every religion appears as a living and developing reality which has undergone different epoch-making overall constellations. Here a first decisive insight is that paradigms can last down to the present, and this is valuable also for Judaism and Islam. This is represented on the diagram by continued lines. This is in contrast to the “exact” natural sciences: the old paradigm (e.g. that of Ptolemy) can be empirically verified or falsified with the help of mathematics and experiment: the decisions in favour of the new paradigm (that of Copernicus) can in the longer term be “compelled” by evidence. But you see in the sphere of religion [(and also art), however,] things are different: in questions of faith, morals and rites (e.g. between Rome and the Eastern Church or between Rome and Luther) nothing can be decided by mathematics or experiment. And so in the religions old paradigms by no means necessarily disappear. Rather, they can continue to exist for centuries alongside new paradigms: the new (the Reformation or modernity) alongside the old (of the early church or of the Middle Ages).

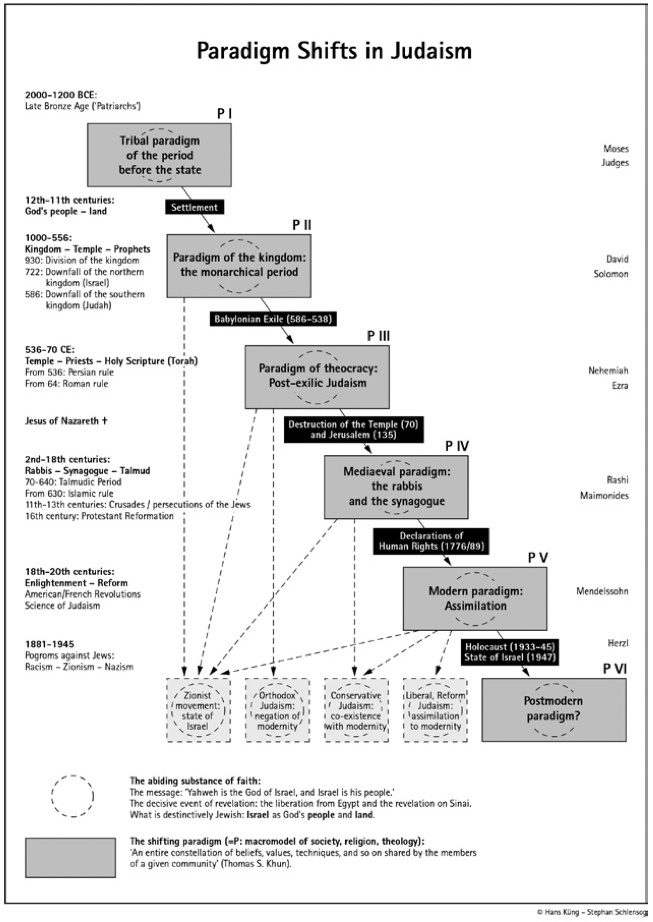

B. Likewise, in Judaism I worked out the macro-paradigms in the history of Judaism (cf. diagram):

- I: the tribal paradigm before the formation of the state;

- II: the paradigm of the kingdom: the monarchical period;

- III: the paradigm of theocracy: post-exilic Judaism;

- IV: the medieval paradigm: the rabbis and the synagogue;

- V: the modern paradigm: assimilation;

- VI: the ecumenical paradigm of post-modernity?

Second insight: The persistence and rivalry of different paradigms is of utmost importance in assessing the situation of religions. This is a second important insight. Why? To the present day people of the same religion live in different paradigms. They are shaped by ongoing basic conditions and subject to particular historical mechanisms. Thus for example there are still Catholics in Christianity today who are

living spiritually in the thirteenth century (contemporaneously with Thomas Aquinas, the mediaeval popes and an absolutist church order). There are some representatives of Eastern Orthodoxy who have remained spiritually in the fourth/fifth century (contemporaneously with the Greek Church fathers). And for some Protestants the pre- Copernican constellation of the sixteenth century (with the Reformers before Copernicus, before Darwin) is still normative.

This persistence is confirmed if we look now at the paradigm changes of Judaism and Islam, also in Judaism and Islam people live in different paradigms.

In a similar way some Arabs still dream of the great Arab empire and wish for the union of the Arab peoples in a single Arab nation (Pan-Arabism). Others prefer to see what binds the peoples together not in Arabism but in Islam, and prefer a “Pan-Islamism.” Some Ultra- Orthodox Jews see their ideal in mediaeval Judaism and reject [even] a modern state of Israel. Conversely many Zionists strive for a state within the frontiers of the empire of David and Solomon which lasted however only a few decades.

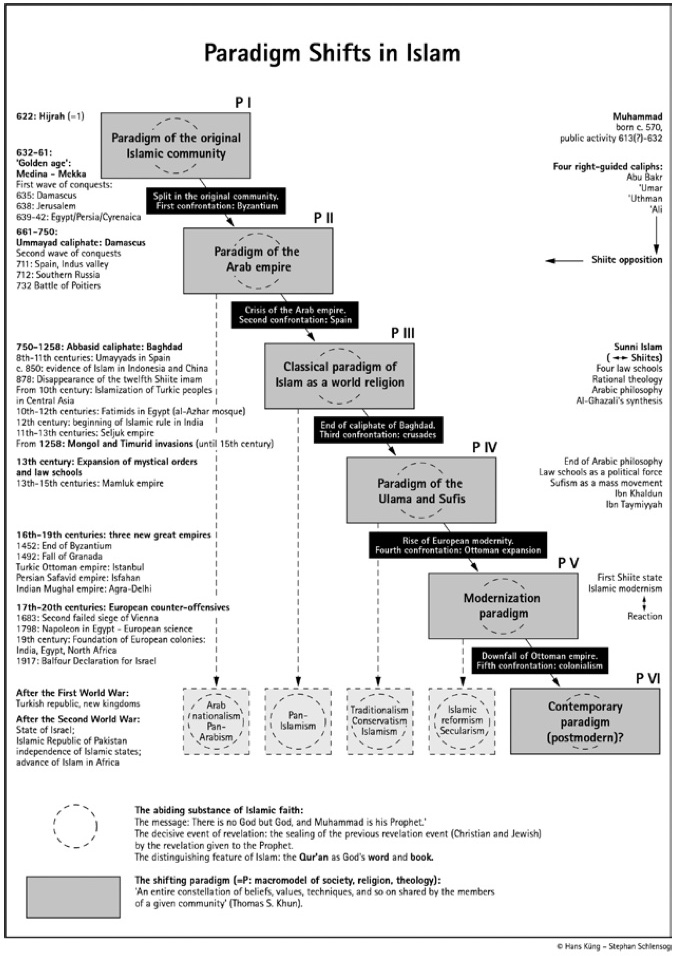

C. Finally in my book on Islam, which will be published in October 2006 by Oneworld, Oxford, I also demonstrate the macro- paradigms in the history of Islam (cf. diagram):

- I: the paradigm of the original Islamic community;

- II: the paradigm of the Arab empire;

- III: the classic paradigm of Islam as a world religion;

- IV: the paradigm of the Ulama and Sufis;

- V: the Islamic paradigm of modernisation;

- VI: the ecumenical paradigm of post-modernity?

Third insight: It is precisely this lasting quality, this persistence and rivalry of former religious paradigms today, that must be one of the main causes of conflicts within the religions and between the religions, the main cause of the different trends and parties, the tensions, disputes and wars. The third important insight that emerges is that for Judaism,

Christianity and Islam the central question proves to be: how does this religion react to its own Middle Ages (at least in Christianity and Islam seen as the “great time”), and how does it react to modernity, where one sees all three religions forced onto the defensive? After the Reformation, Christianity had to undergo another paradigm shift, that of the Enlightenment. Judaism after the French Revolution and Napoleon experienced the Enlightenment first, and as a consequence, at least in Reform Judaism, it experienced also a religious reformation. Islam, however, has not undergone any religious reformation and so to the present day has quite special problems also with modernity and its core components, freedom of conscience and religion, human rights, tolerance, democracy.

III. Present-daychallenges

You may have experienced it yourselves:

Many Jews, Christians and Muslims who affirm the modern paradigm get on better with one another than with their fellow-believers who live in other paradigms. Conversely Roman Catholicism [e.g.], imprisoned in the Middle Ages, can ally itself better for example in questions of sexual morality with the “mediaeval” element in Islam and in Judaism (as at the UN population conference in Cairo in 1994).

Those who want reconciliation and peace will not be able to avoid a critical and self-critical paradigm analysis. Only thus is it possible to answer questions like these: Where in the history of Christianity (and of course also of the other religions) are the constants and where the variables, where is continuity and where discontinuity, where is agreement and where resistance? This is a fourth insight. What has to be preserved is, above all the essence, the foundation, the nucleus of a religion, and from that the constants given by its origin. Constant belief in Christian spirit, law of celibacy: variable. What need not necessarily be preserved is everything that is not essential in the light of the beginning, what is shell and not kernel, what is structure and not foundation. All the different variables can be given up (or conversely developed) if that proves necessary.

Thus in the face of all the religious confusion, particularly in the age of globalisation, a paradigm analysis helps towards a global orientation. Beyond question we find ourselves in a tricky closing phase for the reshaping of international relations, the relationship between the West and Islam, and also the relationships between the three Abrahamic religions - Judaism, Christianity and Islam. The options have become clear: either rivalry of the religions, clash of civilisations, war of the nations - or dialogue of civilisations and peace between the nations as a presupposition for peace between the nations. In the face of the deadly threat to all humankind, instead of building new dams of hatred, revenge and enmity, we shouldn’t be tearing down the walls of prejudice stone by stone and thus be building bridges of dialogue, bridges particularly towards Islam.

IV. The three religions contribute to a global ethic

It is vitally important for this bridge-building that different though the three religions are, and different again the various paradigms which shift in the course of centuries and millennia, at the ethical level there are constants which make such bridge-building possible.

Since human beings have developed from the animal kingdom and become human, they have also learned to behave humanely and not inhumanely. But despite the use of reason which has now developed, because of the drives in human beings the beast in them has remained a reality. And time and again human beings have had to strive to be humane and not inhumane.

Thus in all religious, philosophical and ideological traditions there are some simple ethical imperatives of humanity which have remained of the utmost importance to the present day:

- – “You shall not kill - or torture, injure, rape”, or in positive terms:

- “Have respect for life”. This is commitment to a culture of non-

- violence and respect for all life.

- – “You shall not steal - or exploit, bribe”, corrupt, or in positive terms:

- “Deal honestly and fairly”. This is commitment to a culture of

- solidarity and a just economic order.

- – “You shall not lie - or deceive, forge, manipulate”, or in positive

- terms: “Speak and act truthfully”. This is commitment to a culture

- of tolerance and a life of truthfulness.

- – And finally, “You shall not commit sexual immorality - or abuse,

- humiliate or devalue your partner” or in positive terms: “Respect

- and love one another”. This is a commitment to a culture of equal

- rights and partnership between men and women.

These four ethical imperatives, which are to be found in Patanjali, the founder of Yoga, as in the Buddhist canon, the Hebrew Bible, the New Testament and the Qur’an, are based on two ethical basic principles:

- – First of all there is the Golden Rule, framed many centuries before

- Christ by Confucius and known in all the great religious and

- philosophical traditions, though it is by no means a matter of course:

- “Do not do unto others that which you do not wish be done unto

- yourself”. Elementary though this rule is, it is helpful for deciding

- in many difficult situations.

- – The Golden Rule is supported by the rule of humanity, which is

- not at all tautological: “Every human being, whether young or old,

- man or woman, disabled or not- disabled, Christian, Jew or Muslim

- should be treated humanely and not inhumanely”. Humanity, the

- humanum, is indivisible.

From all this it become clear that a common human ethic or global ethic is not meant to be an ethical system like those of Aristotle, Thomas Aquinas or Kant (“ethics”) but some elementary ethical values, criteria and attitudes which are to form the personal moral conviction of the human person and society (“ethic”).

Of course, this ethic goes against the facts: its imperative of humanity will not be fulfilled a priori, but must be called to mind and realised time and again. However, As Kofi Annan said in his Global Ethic Lecture in Tübingen in 2003: “But if it is wrong to condemn a particular faith or set of values because of the actions or statements of some of its adherents, it must also be wrong to abandon the idea that certain values are universal just because some human beings do not appear to accept them”.

Let me conclude with the very words which the General Secretary of the United Nations also concluded his speech: “Do we still have universal values? Yes, we do, but we should not take them for granted.

- They need to be carefully thought through.

- They need to be defended.

They need to be strengthened”.

And we need to find within ourselves the will to live by the values we proclaim - in our private lives, in our local and national societies, and in the world.

Christianity as a Factor in Global Politics

Paper Presented by Professor Hans Küng

Emeritus Professor, Tübingen University, May 2007

There is more than one Christianity, just as there is more than one Judaism and more than one Islam. Different ‘Christianity’ have emerged from different historical constellations which have very different forms and also very different political effects: Roman Catholic, Orthodox and Reformation Christianity, to mention only the main forms. But Christianity in particular must also be seen in the context of the other religions, since there are some principles which apply to them all.

I. Preliminary remarks on the religions as a factor in global politics

1. A distinction must be made between religion and superstition:

throughout, the Marxist critique of religion identified religion with superstition. However, religion does not recognise as an absolute authority anything relative, conditional and human but only the Absolute itself, which in our tradition since time immemorial we have called ‘God’. By God I mean that hidden Reality, first of all and last of all, which is worshipped not only by Jews and Christians but also by Muslims, and which Hindus seek in Brahman, Buddhists in the Absolute and, of course, also traditional Chinese in Heaven or in Dao. Indeed, the adherents of all religions express it, each in their own concepts and ideas.

By contrast, superstition recognises as an absolute authority something that is relative and not absolute (and requires blind obedience to it). Superstition divinises either material realities (money, power, sex) or a human person (Stalin, Hitler, Mao, the Supreme Head of State and the Pope) or a human organisation (Party, Church). In this respect, for example any cult of persons also shows itself to be a kind of superstition! Consequently not all superstition is religion; there are also un-religious, very modern forms of superstition. Conversely, not all religion is superstition; there is true religion. But any religion can become superstition wherever it makes a non-essential essential, turns a relative into an absolute.

2. Freedom of religion holds for both believers and non-believers: no one may be physically or morally compelled to accept a particular religion or a particular ideology. Everyone must be allowed to leave or change their religion. Article 18 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights has stated this in a binding way. There was not always freedom for atheists: but atheists must be given freedom of thought, speech and propaganda even in countries whose constitution has a religious orientation. And there was also not always freedom for religious people: but believers of all religions must be given freedom of thought, speech and propaganda in all countries, whether these are secular, socialist, Islamic or of any other orientation.

3. Any religion can be exploited and misused politically: in our day the religions are again appearing as agents in global politics. It is true that the religions have far too often shown their destructive side in the course of history. They have stimulated and legitimated hatred, enmity, violence, indeed wars. But in many cases the religions have stimulated and legitimated understanding, reconciliation, collaboration and peace. In his big book on the potential of the religions for peace, Dr. Markus Weingardt of the Global Ethic Foundation has investigated six central case studies and more than 30 examples of mediations in conflicts with a religious basis. And in a book published in the 1990s Dr. Günther Gebhardt emphasised the potential for education towards peace in religious peace movements. In recent decades, all over the world heightened initiatives of inter-religious dialogue and collaboration between religions have developed. In this dialogue the religions of the world discovered that their own basic ethical statements support and deepen those secular ethical values which are contained in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. At the 1993 Parliament of the World’s Religions in Chicago, more than 200 representatives from all the world religions for the first time in history declared their consensus on some shared ethical values, standards and attitudes as the basis for a global ethic.

4. The three monotheistic religions are particularly exposed to the temptation of engaging in violence: all three prophetic religions - Judaism, Christianity and Islam - see themselves today confronted with the accusation that as ‘monotheistic’ religions they are more exposed to the temptation to engage in violence than ‘polytheistic’ and “non-theistic” (Buddhism) religions. Could it be that while every religion as such already contains aspects of violence, because of their tie to a single God, monotheistic religions are especially intolerant, un-peaceful and ready for violence?

But we have to note soberly that ever since there have been human beings there has been religion, and ever since there have been human beings there has also been violence: a non-violent paradisal society has never existed in this human world, which grew by evolution out of the animal world. Down the generations human beings had to try out and test elementary ethical norms to prove them - these included having reverence for the life of others, not killing other people with base intent, in other words not murdering.

However, time and again religions have legitimated and waged wars, indeed even declared ‘holy wars.’ By ‘holy wars’ I mean offensive wars which are waged with a missionary claim on behalf of a deity. Whether this is in the name of one God or several gods is of secondary importance. Of course, it would be wrong to say that all the wars waged by ‘Christians’ in recent centuries have religious motivations. When white colonialists in South and North America and in Australia killed countless Indians and Aborigines, when German colonial masters in Namibia killed tens of thousands of Hereros, when British soldiers shot Indian protesters in large numbers, the Israeli army in Lebanon or Palestine killed hundreds of civilians, or Turkish soldiers hundreds of thousands of Armenians, that truly should not be foisted on belief in one God - not to mention the two World Wars.

5. Every religion must reflect critically on its own religious tradition: in a time when, unlike in antiquity and the Middle Ages, humanity can destroy itself by novel technological means, all religions, and in particular the three prophetic religions which are often so aggressive, must be concerned to avoid wars and promote peace. A differentiated re-reading of one’s own religious traditions is unavoidable here. Two pointers stand out:

First: the warlike words and events in one’s own tradition should be interpreted historically, on the basis of the situation at the time, but without excusing them. That applies to all three religions:

- - The cruel ‘wars of Yahweh’ and the inexorable psalms of vengeancein in

- the Hebrew Bible can be understood from the situation of the

- settlement and from later situations of defence against far superior enemies.

- - The Christian missionary wars and the ‘crusades’ are grounded in

- the situation of the church ideology of the Early and High Middle Ages.

- - The calls for war in the Qur’an reflect the concrete situation of

- the Prophet Muhammad in the Medinan period and the special

- character of the surahs revealed in Medina. The calls to fight against

- the polytheistic Meccans cannot be transferred to the present time to

- justify the use of violence in principle.

Secondly: the words and actions which make peace in each tradition should be taken seriously as impulses for the present. The following ethical principles in the question of war and peace should be noted in respect of a better world order:

- - In the twenty-first century, too, wars are neither holy nor just nor

- clean. Given the immense sacrifice of human lives, the immense

- destruction of the infrastructure and cultural treasures and the

- ecological damage, even modern ‘wars of Yahweh’ (Sharon),

- ‘crusades’ (Bush) and ‘jihad’ (al-Qaida) are irresponsible.

- - Wars are not a priori unavoidable: better co-ordinated diplomacy

- supported by efficient arms control could have prevented both the

- wars in Yugoslavia and the two Gulf Wars.

- - An unethical policy of national interests - say over the oil reserves

- or for hegemony in the Middle East - amounts to complicity in the war.

- - Absolute pacifism, for which peace is the highest good, to which

- everything must be sacrificed, cannot be realised politically and

- can even be irresponsible as a political principle. The right to self-

- defence is explicitly affirmed in Article 51 of the UN Charter. Peace

- at any price, if say a new Holocaust or genocide threatens, is therefore

- irresponsible. Megalomaniac dictators and mass murderers (Stalin,

- Hitler) must be resisted.

- - Crimes against humanity belong before the International Court of

- Justice, which hopefully the American administration following

- that of George W. Bush will finally support in the best American tradition.

In what follows I now want to look more specifically at the roles of the Roman Catholic Church, then the Eastern Orthodox Church and finally the Protestant churches in politics.

II. The Roman Catholic Church as a political factor

The Roman view of Christianity (which is fond of claiming to be the Catholic view) was prepared for in the fourth/fifth centuries, theologically by Augustine and politically by the Roman Popes after the imperial residence was transferred to Constantinople. Only in the eleventh century was it implemented by the Popes of the Gregorian Reform (Paradigm III) with the help of the Pseudo-Isidoran forgeries. At the centre of the Roman vision stands the Bishop of Rome, the Pope, who with an appeal to God and Jesus Christ claims absolute universal rule over the church (and for a time claimed rule over society as a whole): both a normative competence in interpreting doctrine and also a legislative, executive and judicial authority in the life of the church.

As early as the eleventh century this absolutist claim to power (of course together with other factors) led to conflict (the ‘Investiture Controversy’) with the German emperors and a split between a Latin church in the West and a Byzantine-Orthodox church in the East; then in the sixteenth century to the splitting of the church in the West into the churches of the Reformation and the Counter-Reformation Roman Church; and finally, in the nineteenth/twentieth centuries, to the polarisation, to the alienation, indeed to the conflicts between the hierarchy orientated on Rome and the Catholic people and clergy, all of which is also reflected in theology.

In the second half of the twentieth century, the Second Vatican Council in practice adopted many of the central concerns both of the Reformation (P IV) and of modernity (P V), but as a result of the compromises and half-measures extorted by the Roman Curia in many respects failed to realise a consistent Catholic vision of the church for the twentieth century. The collegiality of the Pope with the bishops resolved on in 1965 as a counterbalance to the definition of primacy by the First Vatican Council (1870) was ignored by the Roman Curia after the Second Vatican Council, and papal absolutism was restored and staged in grand style with the help of the mass media.

Almost all over the world the Catholic Church remained a spiritual power, indeed a great power, which neither Nazism nor Stalinism nor Maoism could annihilate. Quite apart from its great organisation, on all the fronts of this world it also has a basis which is unique in its breadth, of communities, hospitals, schools and social institutions, in which an infinite amount of good is done despite all the difficulties, in which many pastors wear themselves out serving their fellow men and women, in which countless women and men devote themselves to young and old, the poor, the sick, the disadvantaged and the failures. This is a worldwide community of believers and committed people. Such commitment is time and again effective politically: in many situations of oppression and injustice it is the commitment of Christians grounded in faith - sometimes even at the cost of their lives - that brings about changes. Catholic groups and individuals played an important role in overthrowing dictatorships in South America and the Philippines.

However, the history of the Catholic Church, like that of other institutions, is also ambivalent. We all know that behind efficient organisation is often an apparatus of power and finance operating with extremely worldly means. Behind imposing statistics, great occasions and liturgies involving vast crowds of Catholics there is all too often a superficial traditional Christianity which is poor in substance. Often a set of clerical functionaries who always have an eye on Rome, who are servile to those ‘above’ and high-handed to those ‘below’, manifests itself in the disciplined hierarchy. A long- outdated authoritarian, unbiblical scholastic theology is often there in the closed dogmatic doctrinal system. And the highly-praised Western cultural achievement is accompanied by all too much secularisation and deviation from the real spiritual tasks.

A pastoral ministry of the Bishop of Rome to the whole church, following the example of the apostle Peter, can be meaningful if it is exercised selflessly in the spirit of the gospel. Nor can it be disputed that the Papacy has done great service in maintaining the cohesion, unity and freedom of at least the Western churches. And the Roman system has often proved itself to be more efficient than the somewhat loose church alliance of the Eastern churches. To the present day, wherever the Pope has credibility, he can address the conscience of the whole world as a moral authority. But the dual spiritual-political role of the Vatican as church government and sovereign state is highly ambivalent. A baneful mixture of the two becomes visible when the Vatican attempts to impose its moral ideas as policy, for example in problems like AIDS or birth control. The 1994 World Population Conference in Cairo is one example of this.

So the weaknesses and defects of the Roman system are manifest, and considerably limit the influence of the Pope, even in his own “sphere of rule”. Many Catholics, too, criticise the Roman claim to power, pointing out that the Roman system has time and again developed away from the original Christian message and church order. Since the High Middle Ages the negative sides have been evident. Since this time there have been complaints about:

- - the authoritarian-infallible behaviour in dogma and morality;

- - the impositions on laity, clergy and local churches, down to the

- smallest detail;

- - the whole fossilised absolutist system of power, which is orientated

- more on the Roman emperors than on Peter, the modest fisherman

- from Galilee.

The opportunities for the Catholic Church: from the Roman perspective it is not denied that often a crumbling church is hidden behind the brilliant Catholic façade. The tremendous crowds which gather on church occasions give an impression, which can easily be deceptive, of an inner power of faith which holds together the Catholic Church as the most significant religious multinational in the world. In Rome it is thought that the reforms within the church called for by many would not advance the Catholic Church further than the Protestant churches, all of which have met these demands for reform and are no better off as a result. Rather, the church grows where it draws on its own positive sources of life, where its great impulses are experienced as a present power derived from looking towards God and encountering Jesus Christ.

From an ecumenical perspective it is a matter of course to affirm the need to concentrate on the essentials of Christianity - God and Jesus Christ. But because the evangelisation campaign initiated by John Paul II decades ago was bound up with long-outdated dogmatic positions and moral demands and was in practice a campaign of re-Catholicisation, it has failed: despite an immense number of documents, speeches and trips and a vast amount of media propaganda the Pope did not succeed in convincing a majority of Catholics of the Roman positions on any of the disputed questions, especially those of sexual morality (contraception, sexual intercourse before marriage, abortion).

So there should also be a warning against false hopes: the crowds present at great church events should not disguise the fact that here there are not only many who are curious and are looking for meaning, but above all people from traditional folk Catholicism. The young people come above all from those conservative ‘movimenti’ native to Spain, Italy and Poland which stand out above all for their veneration of the Pope, not for following his moral commandments and for their greater commitment in their home communities. Despite decades of indoctrination, only a small minority even of them observe the prohibition of pills and condoms. The abortion figures are alarming, particularly in countries where the church has banned the pill.

The traditional Greek-Hellenistic dogmas of the fourth/fifth centuries, like those of the Counter-Reformation dogmatist of the sixteenth century, are virtually unknown to the average Catholic. Moreover the four new Vatican dogmas – the Immaculate Conception (1854) and Assumption (1870) of Mary, the primacy of papal jurisdiction and infallibility (1870), are also largely ignored, if not put in question, in the Catholic Church. Thus a great external and internal emigration from the Catholic Church has taken place, particularly in the traditionally Catholic countries. Moreover because of the rejection of marriage for priests and the ordination of women priests and because of the authoritarian Roman system, soon half of all parishes world-wide will be without a pastor, and the pastoral care built up over centuries will collapse. In Latin America, countless millions of Catholics have immigrated into Pentecostal churches (not all of which can be dismissed as ‘sects’) because they have found inspiring preachers and living communities ready to help there.

In particular the fundamental deficiencies in the Roman system, which is to be distinguished from the Catholic Church as such, make a reconciliation with the Orthodox Churches of the East and those of the Reformation seem difficult.

III. The Orthodox Church of the East as a political factor

The Orthodox Church of the East is beyond doubt closer to earliest Christianity in many respects. The foundations of the Greek- Hellenistic paradigm of the old Roman imperial church (II) were already laid by the apostle Paul after the Jewish Christian paradigm (I). This early church still has no centralist government like that of the later Roman Catholic Church of the West (III). It allows at least priests to marry, though not bishops, so that the latter are mostly taken from the monastic orders. In the Orthodox Church the faithful also receive the Eucharist in two forms, bread and wine. And the Orthodox Church has held out under all political systems, in Russia even during the last persecution under the Communist regime which lasted for seventy years, with thousands of martyrs. That is above all because of its splendid liturgy and its hymns. All this strikes even someone from the West.

However, we also cannot overlook the fact that on the other hand the distance from earliest Christianity is enormous. The average believer has difficulties in recognising Jesus’ last supper in the Byzantine and Russian court liturgy. One particular danger of the Orthodox Church, though, lies in the fact that it is a state church, in which under emperors, tsars and general secretaries the church could become a pliant instrument of the state or the party. The symphony model of state and church which came into being in Byzantium shows clearly that the dependence of the Russian Orthodox Church on the political regime of the time, a dependence which still exists today, has a particularly long and hallowed tradition. It is not only in line with the Muscovite state church which formed in the fifteenth/sixteenth centuries but also has deep roots in the Byzantine tradition, indeed already in Emperor Constantine after the change to Christianity in the fourth century. The Byzantine-Slavonic state-church tradition also explains why most Orthodox churches proved mistrustful of the ideas of 1789, the ideas of democracy, the separation of church and state, freedom of conscience and religion, and so on.

This danger is accentuated in modern nationalism. Granted, for the people under Ottoman rule, for centuries the church formed the last stronghold for the memory of their own identity and independence, so the church had the function of constituting and legitimising the nation. But in the more recent history of Orthodoxy the nationalistic ideology which emerged from that served often enough to inflame ethnic rivalries rather than to dampen them down and keep them under control. Developments in former Yugoslavia assumed such fanatical dimensions not least because for centuries the churches had encouraged nationalism instead of taming it: the Catholic Church encouraged the nationalism of the Croats, the Orthodox Church that of the Serbs. Certainly there is also nationalism in Poland, Ireland and certain Protestant countries. But if there is a special temptation and danger in the world of Orthodoxy, it is less authoritarianism (Roman Catholic) or subjectivism (modern Protestant), as in the West, than nationalism!

The opportunities for the Eastern Orthodox Church: from a Roman perspective the Eastern churches stand relatively close to the Roman Catholic Church. Because of their common past in the first millennium, both have a common structure: episcopal churches which are founded on the apostolic succession, an uninterrupted chain of laying on of hands in the ordination of bishops and priests. Then because of its strong dogmatic and liturgical identity, Orthodoxy is relatively peaceful, though it too is affected by the pressure of secularisation, for example in the former Soviet empire, which alienated more and more people from it. On top of this there is the classic problem of all autocephalous churches (churches with their own supreme head): they are always in danger of political dependence and identification with the nation, whether the Greek, Russian, Serbian nation or any other. Precisely for that reason a reunion with the great Catholic Church - of course under Roman supremacy - would be very useful for the Orthodox churches and is a goal to be striven for by churches on both sides. That is how people think in Rome.

However, from an ecumenical perspective an abolition of the mutual excommunication and a restoration of communion in the Eucharist - already expressed in theory after Vatican II but not realised in practice - would be a task of the first order. Given the necessary respect for frontiers and the Orthodox self-awareness, a course shared with the Catholic Church would avoid the dangers of a national or an ethnic religion. Moreover the anthropological foundations of human dignity, human rights and human responsibilities would be more recognisable from a shared Christian faith and would thus present to the world a shared ethic with universal validity.

Here too it is necessary to warn against false hopes: all the features of dogma, liturgy and church law that the Roman Catholic Church and the Orthodox Church have in common cannot disguise the fact that Rome’s claim to primacy over the East which has been made since the eleventh century is the central insuperable obstacle to a reunion between the church of the West and the church of the East, supported by an infallibility in doctrine defined in the nineteenth century. Broad areas of Orthodoxy see these new dogmas as the real heresy of the Roman Church, which conflict with the New Testament and the joint Christian tradition of the first millennium. And the arbitrary appointment of Roman Catholic bishops on Russian territory after the political change, in Siberia and even in Moscow, and thus the establishment of a Roman hierarchy in parallel to the Orthodox hierarchy, has confirmed all the East’s fears of Roman imperialism.

So a papal visit to Moscow has so far not been wanted (there has been no invitation from Putin). And Benedict XVI’s visit to the Patriarch of Constantinople did not bring any real progress apart from fine ecumenical speeches and gestures. For this Pope, too, did not give any indication that one could replace the mediaeval primacy of jurisdiction - which in any case exists only in Roman theory - with an unpretentious practical pastoral primacy.

Of course, all this does not exclude the possibility that for opportunistic reasons there could be a political alliance between the first Rome and the second (Constantinople), and above all with the third (Moscow). But this would not represent real ecumenical unity, which would presuppose the reciprocal recognitions of ministries and Eucharistic fellowship. Such an alliance would even be ‘unholy’ if it were directed against democracy, freedom of religion and conscience, and the dignity of women (the rejection of the ordination of women); against Protestantism or the World Council of Churches. Such a political alliance would even more reinforce the impression that the Orthodox Church primarily represents a hierarchy which appears through its liturgy, in which in practice the proclamation of the gospel is neglected, as is pastoral work in the community and criticism of society.

IV. The churches of the Reformation as a political factor

The great strength of Protestantism lies in its constantly renewed confrontation with the gospel, with the original Christian message. Concentration on the gospel is the true core of ‘Protestantism’, and this is quite indispensable for Christianity.

Particularly in the twentieth century, people have had the surprising experience that with the Second Vatican Council the Catholic Church, apparently completely fossilised in the Counter-Reformation and anti- modernism, has made a move towards the other Christian churches: it has finally undergone the paradigm change of Protestant Christianity from the Middle Ages to the Reformation in fundamental dimensions, and without giving up catholicity has been concerned to concentrate on the gospel and thus integrate the Protestant paradigm of the Reformation (P IV). A whole series of central Protestant concerns have been taken up by the Catholic Church, at least in principle but often quite practically: a new regard for the Bible, genuine popular worship in the vernacular, the revaluation of the laity, the assimilation of the church to the different cultures and a reform of popular piety. Finally, Martin Luther’s central concern, the justification of sinful men and women on the basis of faith alone, is today as much affirmed by Catholic theologians as is the need for works or acts of love by Protestant theology.

The opportunities for the church of the Reformation: from a Roman perspective, world Protestantism is engaged in a process of rapid change which, to many people seems a disturbing process of decay. The classic confessional churches are rapidly contracting. They have somehow been able to preserve their significance as vehicles of culture, but they are losing importance as religious homes. Often attempts are made to lead the churches out of the crisis with methods of modern management and marketing. But the real forces by which the church lives and on which their being or non-being depends are barely visible. And the more churches continue as mere factors in culture and society, the more they submit themselves to a radicalised enlightenment, the more they dissolve. That is how people think in Rome.

From an ecumenical perspective it is welcome if the Protestant churches sharpen their profile and present their substance more clearly. Every church should preserve its identity and remain a religious home. It should not subject itself to the dictates of a radicalised enlightenment and even adapt itself to and fit in with a process of fusion with modern society. However, the great mistake is not that Protestantism has carried through urgent reforms (the marriage of priests, a more understanding sexual morality, more democratic structures), but that at the same time it has not tackled its poverty of substance and lack of profile decisively enough.

Here too, Rome has false hopes: a church should not chain itself to its own tradition; it should not put either mediaeval or Reformation theology and church law above the confession of Jesus Christ and the discipleship of Christ. For centuries Rome has reckoned with the constant progress of the splitting up, the spiritual emptying and finally the dissolution of Protestantism – in vain. A comparison of Catholic and Protestant theology alone shows how often Catholic theology and the Catholic Church have lagged behind; all the decisive advances in exegesis were first made in Protestant theology. Protestantism is by no means dead even in Europe and North America; there are living communities in both areas.

V. The threat from modernity and fundamentalism

Within the framework of the Protestant paradigm of the Reformation, the fundamentalist movement formed in the nineteenth/twentieth centuries in reaction to modernity (P V). A fundamentalist is someone who confesses the verbal inspiration and therefore the unconditional inerrancy of the Bible at the present time. Someone who in pre-critical times understood the Bible in an uncritical and naïve, literal way is not a fundamentalist.

Fundamentalism took shape in the face of a twofold threat to the traditional understanding of faith: on the one hand there was the world-view of modern science and philosophy, parts of which (especially Darwin’s theory of evolution) were opposed to the picture of the world presented in the Bible. On the other hand, modern biblical criticism, working since the Enlightenment with historical-critical methods, investigated the history of the origin of the books of Genesis and the five books of Moses generally, and also the complex history of the origin of the three synoptic Gospels and the Gospel of John, which is very different from them. So fundamentalism in the authentic sense is a product of a defence and an offensive against modern science, philosophy and exegesis, aimed at rescuing the verbal inspiration and inerrancy of the Bible from the threat posed by modernity.

In the nineteenth century Roman theology, too, with the usual time lag, largely appropriated the doctrine of the verbal inspiration and inerrancy of scripture (which had already been systematised by Protestant orthodoxy). But just as the Roman Inquisition discredited itself with processes against Galileo and others, so American fundamentalism failed when it wanted to prescribe its theory of ‘creationism’ (the creation of human beings directly by God) in state schools.

Most recently, the term fundamentalism has also been extended to other religions, above all Islam and Judaism. Muslims themselves today call exclusivist, literalistic Islam ‘Islamism’, and Jews call exclusivist, literalistic Judaism ‘Ultra-Orthodoxy’. But if one wants to characterise negatively a rigid literalistic faith and a legalistic observance of the law, which are often combined with political aggressiveness, then one speaks of Muslim and Jewish fundamentalism as one speaks of Christian fundamentalism. Of course geopolitical strategies are developed only by Christianity (‘Crusade for Christ’, ‘Re-evangelizing Europe’) and Islam (‘Re- Islamizing the Arab world’). Here the thought-patterns of evangelical hardliners in the USA and Islamic radicals are similar: the political opponent is the embodiment of evil. And the battle of good against evil legitimises even military attacks and invasions. Nor should one forget the religions of Indian and Chinese origin. Hinduism (against Muslims, Christians or Sikhs) or Confucianism (against non-Han Chinese), too, can behave in an exclusivist, authoritarian, repressive, fundamentalist way. In other words: fundamentalism is a universal problem, a global problem.

The opportunities for fundamentalism: what is the source of the enormous effectiveness and thrust of the different fundamentalisms? Three factors are heightened and work together:

- - Consistency: a basic religious value or a basic idea is constructed

- consistently and protected in a perfectionist way for fear of a

- debilitating compromise.

- Simplicity: ways of thinking, attitude and system are simple and - transparent; more sophisticated perspectives are largely excluded

- Clarity: the interpretation and doctrinal structure are unambiguously - set out: any subtle interpretation is rejected as a deviation from pure

- doctrine, indeed as heresy.

But here too we should have no illusions; is there any future in putting forward the doctrine of the verbal inerrancy or infallibility of holy scripture, whether this is the Hebrew Bible (halakhah), the Qur’an or the New Testament (or under certain conditions even the infallibility of the Pope, the Reformers of the Council) as the dogma of dogmas, the formal central dogma on which all other truths of faith depend? Like Judaism and Islam, Christianity seeks to communicate a basic orientation for human life in an age which is poor in orientation. But how can a fundamentalist Christianity offer in the long term an interpretation of existence and the world which embraces all aspects of living in a time which is stamped throughout by modern science, echnology and culture if it is tied to a literal understanding of the account of the creation and the last judgment, fall and redemption?

This reactionary religious view of the world has proved particularly baneful where it has been combined with a reactionary foreign policy. Anyone who admires the America of Lincoln, Kennedy and Martin Luther King, the New Deal, the Marshall Plan, the Peace Corps, the Peace and Civil Rights Movements and the Nobel Peace Prize-winner Jimmy Carter - all representatives of a democratic and humanitarian America lasting over so many centuries - was and is dismayed at the revolutionary reorientation of American foreign policy which was the work of a neoconservative clique of journalists and power politicians (orchestrated by the power of the media). These allied themselves not only with the powerful Israel lobby (AIPAC), but increasingly with the Protestant fundamentalists of the southern states, who under the leadership of the neoconservative intellectuals became George W. Bush’s important power base, with masses of foot soldiers. However, since the last congressional elections and in view of the hopeless Iraq war, with its thousands of victims and debts amounting to billions, the day is again beginning to dawn in the USA.

Hidden religious structures have provided the points of reference in these remarkable new alliances: secularist Jewish neoconservatives (‘neocons’) could thus ally themselves with fundamentalist Protestants (‘theocons’) who, for their part, like George W. Bush, regard the war against terrorism as an apocalyptic fight against ‘evil’ generally, and on the basis of a literalistic understanding of the Bible see the whole of Palestine as the ‘holy land’ given by God to the Jews; for them, however, the state of Israel is merely the presupposition for the return of Christ announced by the New Testament, with the subsequent total conversion of all Jews! The Jewish side often tacitly accepts this anti- Jewish ideology as long as it is of political benefit to the state of Israel and its policy.

But this fundamentalist religious world-view also combined with certain positions of American domestic policy: against abortion, stem cell research and same-sex marriage. Since the election of President Reagan, the ‘religious right’ - i.e. those politically active evangelical Christians - has played a major role in the Republican Party and helped Bush Junior to be elected twice. But recently a backlash can also be noted in domestic politics. Individual leaders of the religious right are showing more understanding for the problems of AIDS, euthanasia (the Terri Schiavo case) and the threat to the environment from climate change.

On a Politician’s Ethics

Speech by H.E. Chancellor Helmut Schmidt

at Tübingen University, 8 May 2007

First, I would like to thank you, dear Hans Küng. I was very pleased to accept this invitation, as I have followed the Global Ethic Project most positively since the start of the 1990s. The words “Global Ethic” may seem too ambitious to some, but the goal, the task to be solved, is truly and, by necessity, very ambitious. Perhaps at this point I can mention that an array of former heads of state and government from all five continents have set themselves a common goal very similar to this one since 1987 as the InterAction Council; however, as yet our work has only had relatively little success. In contrast, the achievements of Hans Küng and his friends are outstanding.

I myself can thank a devout Muslim for first inspiring me to consider the moral laws common to the great religions. More than a quarter of a century has gone by since Anwar Al Sadat, then the President of Egypt, explained the common roots of the three Abrahamic religions to me, as well as their many resemblances, and in particular their corresponding moral laws. He knew of their shared law on peace, for example in the psalms of the Jewish Old Testament, in the Christian Sermon on the Mount or in the fourth sura of the Moslem Qur’an. If only the people were also aware of this convergence, he believed; if only the people’s political leaders, at least, were aware of this ethic correspondence between their religions, then long-lasting peace would be possible. He was firmly convinced of this. Some years later, as the President of Egypt, he took political steps to match his conviction and visited the capital and parliament of the State of Israel, which had previously been his enemy in four wars, to offer and conclude peace.

At my advanced age one has experienced the deaths of one’s own parents, siblings and many friends, but Sadat’s assassination by religious fanatics shook me more severely than other losses. My friend Sadat was killed because he obeyed the law of peace.

I will return to the law of peace in a moment, but first a proviso: a single speech, especially one restricted in length to less than one hour, cannot come close to exhausting the topic of a politician’s ethics. For this reason, today I have to concentrate on a number of comments, namely the relationship between politics and religion, then the role of reason and conscience in politics, and finally the need to compromise, and the loss of stringency and consistency this inevitably entails.

I.

Now let us return to the law on peace. The maxim of peace is an essential element of the ethics or morals which must be required of a politician. It applies equally to domestic policy within a country and its society, and to foreign policy. Along with this, there are other laws and maxims. This naturally includes the “Golden Rule” taught and demanded in all world religions. Immanuel Kant merely reformulated it in his Categorical Imperative; it is popularly reduced to the phrase: “Do as you would be done by”. This golden rule applies to everyone. I do not believe that different basic moral rules apply to politicians than to anybody else.

However, at a level below the key rules of universal morality, there are many special adaptations for specific occupations or situations. Just think of doctors’ respected Hippocratic Oath of doctors, for example, or a judge’s professional ethics; or think of the special ethic rules required of business people, of moneylenders or bankers, of employers or of soldiers at war.

As I am neither a philosopher nor a theologian, I will not make any attempt to present you with a compendium or codex for the specific political ethic, and thus compete with Plato, Aristotle or Confucius.

For more than two and a half millennia, great writers have brought together all kinds of elements or components of the political ethic, sometimes with highly controversial results. In modern Europe this extends from Machiavelli or Carl Schmitt to Hugo Grotius, Max Weber or Karl Popper. I, on the other hand, must restrict myself to presenting you with some of the insights I have gained myself during my life as a politician and a political publicist - for the most part in my home country, and, for the rest, in dealing with our neighbouring countries, both nearby and further away.

At this juncture I would also like to point to my experience that, whereas talk of God and Christianity has been far from rare in German domestic affairs, the same is not true in discussion or negotiation with other countries and their politicians. Recently, when referendums were held in France and the Netherlands on the draft European Union constitution, for many people there the lack of reference to God in the text of the constitution was a decisive motive for their rejection. A majority of politicians had chosen to refrain from invoking God in the text of the constitution. In the German constitution, the Basic Law, God does appear in the preamble: “Conscious of their responsibility before God ...” and later a second time in the wording of the oath of office in Article 56, where it finishes: “So help me God”. However, immediately after, the Basic Law says: “The oath may also be taken without religious affirmation”. In both places it is left up to the individual citizen to decide whether he means the God of the Catholics or of the Protestants, the God of the Jews or the Muslims.

In the case of the Basic Law, it was also a majority of politicians who formulated this text in 1948/49. In a democratic order, under the rule of law, politicians and their reason play the decisive role in constitutional policy, rather than any specific religious confession or its scribes.

We recently experienced how, after centuries, the Holy See finally reversed the verdict against Galileo’s reason, once rendered by power politics. Today, we experience every day how religious and political forces in the Middle East are locked in bloody battles for power over people’s souls - and how reason, the rationality we all possess, repeatedly falls by the wayside. When, in 2001, some religious zealots took their own lives and those of three thousand people in New York, convinced they were serving their God; Socrates’ death sentence - for godlessness! - was already two and a half thousand years in the past. Obviously, the perennial conflict between religion and politics and reason is a lasting element of the human condition.

II.

Perhaps I can add a personal experience here. I grew up during the Nazi period; at the start of 1933 I had only just turned fourteen. During my eight years of compulsory military service I had placed my hopes in the Christian churches for the time after the expected catastrophe. However, after 1945, I experienced how the churches were able neither to re-establish morality nor to re-establish democracy and a constitutional state. My own church was still struggling over Paul’s Epistle to the Romans: “Be subject unto the higher powers”.

Instead, at first some experienced politicians from the Weimar period played a significant part in the new beginning; Adenauer, Schumacher, Heuss and others. However, at the start of the Federal Republic it was less the old Weimarians, and far more the incredible economic success of Ludwig Erhard and the American Marshall aid which swung the Germans towards freedom and democracy and in favour of the constitutional state. There is no shame in this truth: after all, since Karl Marx we have known that economic reality influences political convictions. This conclusion may only comprise a half- truth, but the fact remains that every democracy is endangered if its governing authorities cannot keep industry and labour in adequate order.

As a result, I remained disappointed by the churches’ sphere of influence, not only morally, but also politically and economically. In the quarter of a century since I was Chancellor, I have learned a lot of new things and have read a lot. In this process, I have learned a little more about other religions and a little more about philosophies I was previously not familiar with. This enrichment has strengthened my religious tolerance; at the same time, it has put me at a greater distance from Christianity. Nonetheless, I call myself a Christian and remain in the Church, as it counterbalances moral decline and offers many people support.

III.

To this day, what continues to disturb me about references to the Christian God - both among some church people and some politicians - is the tendency towards excluding others which we come across in Christianity - and equally in other religious confessions, too: “You are wrong but I am enlightened; my convictions and aims are godly”. It has long been clear to me that our different religions and ideologies must not be allowed to stop us from working for the good of all; after all, our moral values actually resemble one another closely. It is possible for there to be peace among us, but we always need to recreate this peace and “establish” it, as Kant said.

It does not serve the aims of peace if a religion’s believers and priests try to convert the believers of another religion and to proselytise to them. For this reason, my attitude towards the basic idea behind missions of faith is one of deep scepticism. My knowledge of history plays a special role in this - I am referring to the fact that, for centuries, both Christianity and Islam were spread by the sword, by conquest and subjugation, but not by commitment, conviction and understanding. The politicians of the Middle Ages; that is, the dukes and kings, the caliphs and the popes, appropriated religious missionary thoughts and turned them into an instrument to expand their might - and hundreds of thousands of believers willingly let themselves be used in this way.

In my eyes, for example, the Crusades in the name of Christ, where soldiers held their Bibles in their left hand and their swords in their right, were really wars of conquest. In the modern age, the Spanish and the Portuguese, the English, the Dutch and French, and finally also the Germans used violence to take over most of the Americas, Africa and Asia. These foreign continents may have been colonised with a conviction of moral and religious superiority, but the establishment of the colonial empires had very little to do with Christianity. Instead, it was all about power and egocentric interest.Or take the Reconquista on the Iberian Peninsula: it was not only about the victory of Christianity, but, at its heart, concerned the power of the Catholic monarchs, Ferdinand and Isabella. When Hindus and Muslims fight today on Indian soil, or when Sunni and Shiite Muslims battle in the Middle East, time after time the crux of the matter is power and control - the religions and their priests are used to this end, as they can influence the masses.

Today it greatly concerns me that at the start of the 21st century a real danger has developed of a worldwide “clash of civilisations”, religiously motivated or in religious guise. In some parts of the modern world, motives of power, under the guise of religion, are mixed with righteous anger about poverty and with envy at others’ prosperity. Religious missionary motives are mixed with excessive motives of power. In this context it is hard for the balanced, restrained voices of reason to gain attention. In ecstatic, excited crowds, an appeal to individuals’ reason cannot be heard at all. The same is true today in places where Western ideologies and teachings on democracy and human rights, which are perfectly respectable, are forced with military might and almost religious fervour upon cultures which have developed in a totally different manner.

IV.

I myself have drawn a clear conclusion from all these experiences: mistrust any politician, any head of government or state, who turns his religion into the instrument of his quest for power. Stay clear of politicians who mingle their religion, oriented towards the next world, with their politics in this world.

This caution applies equally to politics at home and abroad. It applies equally to the citizens of a country and to its politicians. We must demand that politicians respect and tolerate believers from other religions. Anyone who is not capable of this as a political leader must be seen as a risk to peace - to peace within our country as well as to peace with others.

It is a tragedy that, on all sides, the rabbis, the priests and pastors, the mullahs and ayatollahs have, to a great degree, kept all knowledge of other religions from us. Instead they have variously taught us to think of other religions disapprovingly and even to look down upon them. However, anyone who wants peace among the religions should preach religious tolerance and respect. Respect towards others requires a minimum amount of knowledge about them. I have long been convinced that - in addition to the three Abrahamic religions - Hinduism, Buddhism and Shintoism rightly demand equal respect and equal tolerance.

Because of this conviction, I welcomed the Chicago Declaration “Toward a Global Ethic” by the Parliament of the World’s Religions, seeing it not only as desirable but also as urgently necessary. Based on the same fundamental position, ten years ago today the InterAction Council of former heads of state and government sent the Secretary- General of the United Nations a draft entitled “Universal Declaration of Humans Responsibilities” which we had developed on the initiative of Takeo Fukuda from Japan. Our text, written with help from representatives of all the great religions, contains the fundamental principles of humanity. At this point, I would particularly like to thank Hans Küng for his assistance. At the same time, I gratefully recall the contributions made by the late Franz Cardinal König of Vienna.

V.

However, I have also come to understand that, two and a half thousand years ago, some of humanity’s seminal teachers, Socrates, Aristotle, Confucius and Mencius, had no need for religion, even though they paid lip service to it, as they were expected to, more on the margins of their work. Everything we know about them tells us that Socrates based his philosophy, and Confucius his ethics, on the application of reason alone; none of their teachings had religion as a basis. Yet both have come to lead the way, even today, for millions upon millions of people. Without Socrates there would have been no Plato - perhaps even no Immanuel Kant and no Karl Popper. Without Confucius and Confucianism, it is hard to imagine that the Chinese culture and the “Kingdom of Silk”, whose lifespan and vitality are unique in world history, would have existed.